Life Eats Life

The perils of empathizing with food.

I’ve wanted to write about my relationship with food and, in particular, veganism, for some time. After being vegan for most of my adult life—and certain that it would remain a lifelong conviction—I was as surprised as anyone when I decided to abandon the lifestyle after Graham was born. This piece barely scratches the surface of what was an extremely difficult decision (some might say it doesn’t even broach the topic at all), but I feel as if it is a good enough start. Thanks for subscribing and thanks for reading.

Excreting is the curse that threatens madness because it shows man his abject finitude, his physicalness, the likely unreality of his hopes and dreams. But even more immediately, it represents man’s utter bafflement at the sheer non-sense of creation: to fashion the sublime miracle of the human face, the mysterium tremendum of radiant feminine beauty, the veritable goddesses that beautiful women are; to bring this out of nothing, out of the void, and make it shine in noonday; to take such a miracle and put miracles again within it, deep in the mystery of eyes that peer out—the eye that gave even the dry Darwin a chill: to do all this, and to combine it with an anus that shits! It is too much. Nature mocks us, and poets live in torture.

Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

We have evolved to recognize the grotesquery of feces and its expulsion; shit is, of course, not good or safe to eat, and therefore those of our ancestors who were adequately repelled by it possessed an advantage over their brethren whose attitude toward feces was more lackadaisical. On the other hand, nutritive, high-caloric foodstuffs we find irresistibly attractive (sometimes to our own detriment). We are social eaters; we take pictures of our plates and post them to social media; we talk openly and enthusiastically about the hottest culinary trends, diets, restaurants, and so on.

Not so for eating’s unlucky, ugly cousin: scatological snapshots are decidedly unwelcome in most online spaces, and most of us are just as happy for it, grateful for the solidity of the poo taboo. Poop is—and even writing about it, is, to an extent—disgusting. The case I hope to make here, however, is that eating is similarly repulsive, perhaps even more so. “Don’t chew with your mouth open,” children are taught from an early age. Well, why not? For the same reason that we close the bathroom door before using the toilet: because it’s gross. The brute necessity of life’s incessant salivating, chomping, grinding, and swallowing is fundamentally disgusting; we’d rather not be reminded of it.

But—mouths open or closed—there is no escaping it: life eats life. Maddening; paradoxical; obscene: we are sentient, thinking beings, self-aware, but the very perpetuation of our sentience depends inexorably upon the consumption of other beings, many of them sentient in their own right. Just to stay alive, we must saw at flesh with dull teeth, gnaw at gristle and bone. And we must think about it, vaguely aware of the bestiality of our predicament. As if this were not sorry enough a state of affairs life goes on to shit death. This vulgar equilibrium is the only compelling argument for the existence of God—but not, it goes without saying, a benevolent one.

So it went: as the size of our brains increased over ponderous millennia, one generation to the next, we utilized our increased cognition to obtain better food more safely, more reliably, and in greater quantity. Until one day, a painfully, cringingly self-aware ancestor took a bite and thought about what, exactly, he was doing, and he gagged a little before he could stifle the thought.

Anyway. It’s turning out that my son, Graham, is a bit of a picky eater. Not a huge surprise—from the get-go, Graham’s relationship with food has been… complicated. As early as his first month planetside, Hannah recognized that there was something off about the way he nursed. He wasn’t, like some babies, completely incapable of the (surprisingly difficult) feat; nor was he utterly disinterested. He successfully identified Hannah’s nipples as a locale of great importance within his expanding world—even that they were meant to be interacted with orally. Nevertheless, his nursing sessions were reliably short and usually ended in cries of hungry frustration instead of the milk-drunk stupor of a well-fed infant.

We visited our first lactation consultant, Jen, a saint of a woman, a (medical) nurse who worked under the aegis of the local hospital and whose entire practice specialized in the (surprisingly complex) mechanics of breastfeeding. She confirmed what Hannah already suspected: Graham was having trouble ‘latching’ onto momma’s nipples. As a result, he was only drinking Hannah’s letdown, the watery surge of runny ‘foremilk’ that precedes the fattier, harder-to-get ‘hindmilk’. As the name suggests, the letdown practically (and sometimes literally) leaks from the nipple, so it required no real effort or determination on Graham’s part—just catching it in his mouth, basically. But because he couldn’t suck, couldn’t create the requisite vacuum with his mouth, he missed out on all the good stuff, giving up as the trickle subsided.

For most of our evolutionary history, being bad at nursing—sucking at sucking—was a death sentence. During infanthood, mammals rely exclusively on their mother’s milk for all their nutritional needs; the mammalian biological imperative to nurse the young predates the emergence of humans and primates by millions of years and is, therefore, quite powerful, to understate the case by an order of magnitude.1

Luckily for him, Graham was born in the year 2022, in the United States, to parents whose poverty was situational, rather than generational, and so his unskilled sucking was merely a hindrance and a (major) inconvenience; in no way did it spell his doom. (Although the anxiety we felt, as his parents, admitted of no difference, experientially speaking, to that catastrophic panic felt by our ancestors whose young could or would not eat. It was rough.)

Through an absurd and wholly unscientific system of trial and error, we—eventually—devised a routine that seemed to work for him, some of the time. We kowtowed to his exacting preferences: bottles served hot, five degrees Fahrenheit above body temperature, from gimmicky contraptions designed to prevent the gassy discomfort of indigestion. Some days he would attack his bottles with gusto; more often, he would merely attack them.

When we introduced him to solid foods at about six months, he seemed at first to take to it like a pro, but—before long—he woke up to the essential odiousness of ingestion and protested accordingly. All the same, it’s less stressful now than it was at first—at this point, he’s able to communicate his pleasure and displeasure to us with a degree of specificity unavailable to him during those early days. If he decides not to eat for a meal, or even a day, we’re able to set aside our anxiety and trust that his disinterest in food is temporary and that tomorrow, he’ll be hungry.

That’s not quite right; he’s extraordinarily interested in food—perhaps too interested in it to bother eating it. Sitting in his high chair, he’ll exercise his grip by crushing peanut-buttered toast into a pulpy mass; he appears to be developing a folk theory of ballistics, utilizing his rubber spoon to propel cottage cheese or applesauce in majestic, parabolic arcs across the living room. By the conclusion of most of his mealtimes, the concentrations and locales of his various foodstuffs have altered significantly—shapes changed and geographic coordinates dispersed—but very, very little of it is inside of him.

I’m worried he gets this from me.

Let me explain: my relationship with food is fraught and complex. One of my earliest food-related memories involves a protracted battle with my mother over my refusal to eat a sandwich. (I don’t remember what sort of sandwich; it could have been anything.) I might have been four years old, maybe five. The crux of the issue was that I had, for whatever reason, assigned a moral weight to the continued existence of the sandwich my mother had prepared.

My thoughts were not sophisticated enough to argue that the snack was sentient; in my later years as a vegan and vegetarian, I might have brought up the sandwich’s carbon footprint—the greenhouse gases emitted in its production, from seed to plate, the untallied cost of the rainforests slashed and burned to grow it, the fossil fuels combusted to transport it to the grocery store and so on. During my last few years of adhering to a vegan diet, perhaps I’d have resorted to claims about sandwiches being “ends unto themselves”, a Kantian tenet referring to the quality of having one’s own desires and goals that are goods for their possessor. At that age, though, I could not articulate my misgivings; I merely recognized that, if I were to consume the sandwich, it would be at the expense of the sandwich—that such an action would be, in fact, irrevocably detrimental to it.

I don’t remember the extent of my resistance—ten minutes? An hour? It has become one of those cancerous memories I cannot entirely trust, faithless and compromised over decades, now, of frequent access and reproduction. All that remains with vivid certainty is the bitter sting of defeat, for of course the battle was lost; how could I compete with my implacable mother’s razor-sharp sophistry?

Since memory fails, here is how I imagine it went: my dear mother, perhaps frazzled, even growing a bit short-tempered, appealed first to my love for her. “I worked hard to make this for you. It will hurt my feelings if you don’t eat it.” Being, in general, a sensitive and sympathetic child, I was moved by this entreaty—how could I not have been? But—and what my mother failed in that moment and throughout the altercation to understand—it was that very sensitivity that bred my rebellion, that prevented me from eating the sandwich.

The term theory of mind describes the ability to recognize and acknowledge the internal lives of others, despite the fact that we have access only to our own. Noticing that we have an inner world populated with thoughts, feelings, and qualitative experiences, we infer that this must be the same for everyone. Our capacity for empathy, I think, depends on an adequately-developed theory of mind; to simulate the emotions and predict the reactions of people who are not ourselves, we must first be able to recognize possessors of emotions, to distinguish between those entities that have inner lives—and those that do not.

Although this becomes more-or-less second nature to us relatively early on, there are of course misfires as the skill develops—false positives being, at least for myself, the most frequent mistake. And indeed, this was the error at the heart of the whole tragic misunderstanding: I had identified the sandwich as a thinking and feeling being, a person, the sort for whom I was regularly encouraged to empathize with, whose feelings I was told I ought to consider.

And I had been taught well. My parents received regular compliments on my behavior—delighted squeals of so polite! and adoring he’s so considerate! My habit of developing and imagining elaborate inner lives for each of my stuffed animals was similarly encouraged, and why not? Graham’s not doing this yet, but I can anticipate how heartbreakingly precious it will be when he does.

So when my mother appealed to my consideration for her feelings, a fatal conflict was introduced: suddenly, I had to decide between hurting her, and killing the sandwich. It was not even that I had to harden my heart; as the conflict dragged on, I would have loved to merely side with her, the inevitable victor, to acquiesce to her increasingly-impatient demands and return from the cold wilderness of her anger into the soothing comfort of her favor. I just could not muster the requisite brutality to do the thing she wanted of me; I lacked the constitution and the stomach for it.

Perhaps there are vast sections of the memory unavailable to me, hours of begging and pleading, ineffectual platitudes about starving children in Africa or elsewhere. There must have been. There must have been some extenuating circumstance, some looming consequence that I could not see and thus cannot now recall. Given the sheer barbarism of what came next, nothing else makes sense. My mother’s exact wording is lost from memory, but I remember with devastating clarity the spirit of the rhetorical thrust that finally pierced my moral resistance, that broke the siege and ended my strike:

You have to eat it or you’ll die.2

Because I cannot bring to mind the extenuating circumstances that presaged her (somewhat nuclear) retort, I will render no verdict as to the appropriateness of its mobilization. There is a sense in which my mother’s strategy was to bring, as it were, a gun to a knife fight, but I do not suppose that she intended to threaten my life. Charitably, I reckon that it was a last resort, marshaled only after exhausting all civilized recourse. Perhaps I had offered up similar instances of lunchtime resistance for days or even weeks prior. I was very young; I do not remember.

This brings us to the cornerstone of the memory, the qualitative, narrative sequence that I remember in the first person. I’m crying, probably tired from the extended struggle, and—although I don’t remember being hungry—given the circumstances, it makes sense to assume that I could have been virtually famished. I gripped with both hands the sandwich, the soft white bread of its limbs giving beneath my tiny fingers. Through my tears, I apologized to the sandwich. Here, I can provide an exact quote, the fidelity of which there can be no real question:

I’m sorry, little Sandwich, but I have to eat you.

It’s important to draw attention to the extent to which I had anthropomorphized the sandwich; in that moment, there was no emotional difference between the brutality of what came next and, say, the desperate meals of the Donner party. I steeled myself, hardened my heart against the snack to which I had become so inexplicably attached, raised it to my open mouth, and bit down suddenly and viciously, as if I were trying to kill the thing with the first blow. Immediately my tears returned, but here the memory dissolves almost entirely; perhaps I finished consuming my former friend; perhaps a single bite was all my mother required of me, a merely symbolic act of acquiescence, a communion that absolved her prodigal son.

I am skeptical of the word “trauma.” Not because I am a cynic; I am, but it does not prevent me from recognizing that people develop defense mechanisms—psychological and physiological—in response to specific events in their lives. Like the sapling that grows unnaturally around a stone becomes a crooked, gnarled tree, the pathologies of childhood are writ large upon our adult neuroses, as maladaptive patterns of behavior or beliefs. I am skeptical of trauma because of its explanatory power: like religion, astrology, or psychoanalysis, it can extend to explain everything within the domain of human behavior, with entire personalities reduced to the ‘traumas’ that generated them. Applicability extended thusly, it of course explains nothing.

Nevertheless, I wonder now if the brutality of my sandwich lunch that day traumatized me. I can’t help but try to explain vast swathes of my adult life in relation to it, as if everything I’ve done—everything I am—can somehow be traced back to that fateful meal. It sounds crazy, but sometimes I worry that the trauma is generational. I’m afraid that my despicable act, so many years ago, burrowed its way into my germline and that the wages of my ancient sin are now being visited upon my son.

And I have fever dreams—sleep-deprived, waking nightmares—during which Graham refuses any sustenance whatsoever, not because of some physiological contingency or developmental delay, but out of a burdensome capacity for love, swollen like a tumor. Because he knows—not consciously, but on some tacit level—that to love something means to desire its continued existence, and thus we cannot eat what we also love. In the dream, I want to cajole him, lie to him, to tell him it’s okay, but he doesn’t understand because he’s just a baby boy. Desperate, I feel the terrible truth come surging up from my stomach like vomit, like a meal half-digested and rejected: you have to eat it or you’ll di…

And then I wake up.

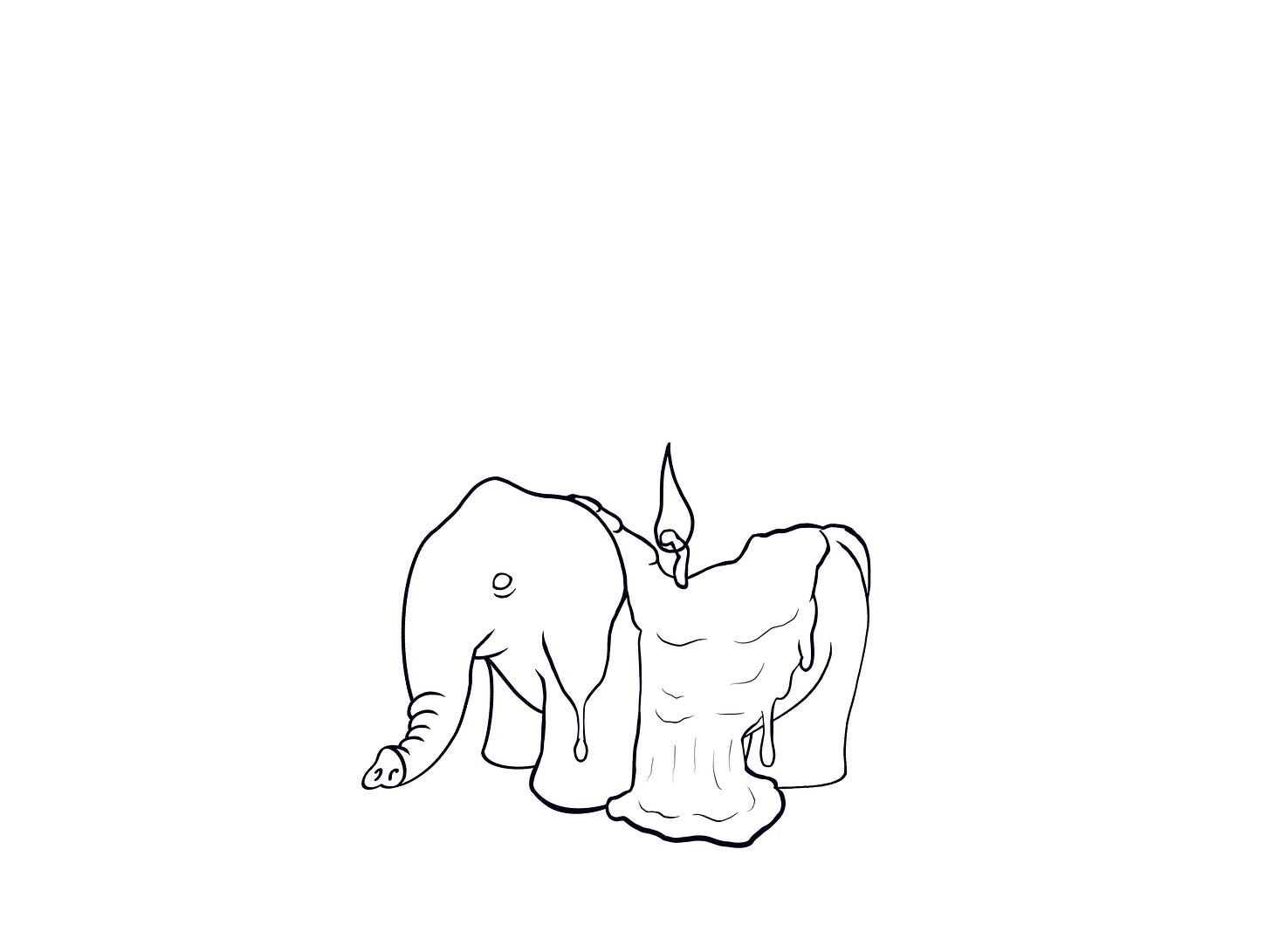

Thanks for reading. I hope you’ve enjoyed this episode of White Elephant. As always, you can reach me at benjimahaffey@substack.com. Thanks to my brother for the truly chilling sandwich illustration, as well as the section-divider elephant candles. He also provided me with some feedback for this essay, which was fun and helpful.

It’s also of note that sucking—nursing at mother’s teat—is somehow not disgusting. The toothless, wet mouth of a newborn is innocence entire; the filth and sin of grinding molars are taken up by the Christlike mother; she must bite; she must chew; she must tear, mash, pulverize, and swallow. The babe is, for a time, exempted from this unpleasant necessity, and—as a result—even his bowel movements during this period are inoffensive and, though not quite pleasant to work around, qualitatively unlike those reeking logs cut from adult cloth.

This is, as I said, not an exact quote; it is somewhere in between Tim O’Brien’s notion of “story truth”, which utilizes fiction to derive truths too universal for mere fact-finding, and autobiography. She said something like that; the gist was plainly that, were I to continue to protest after the same fashion, my own death would necessarily follow.