Gedankenexperiment

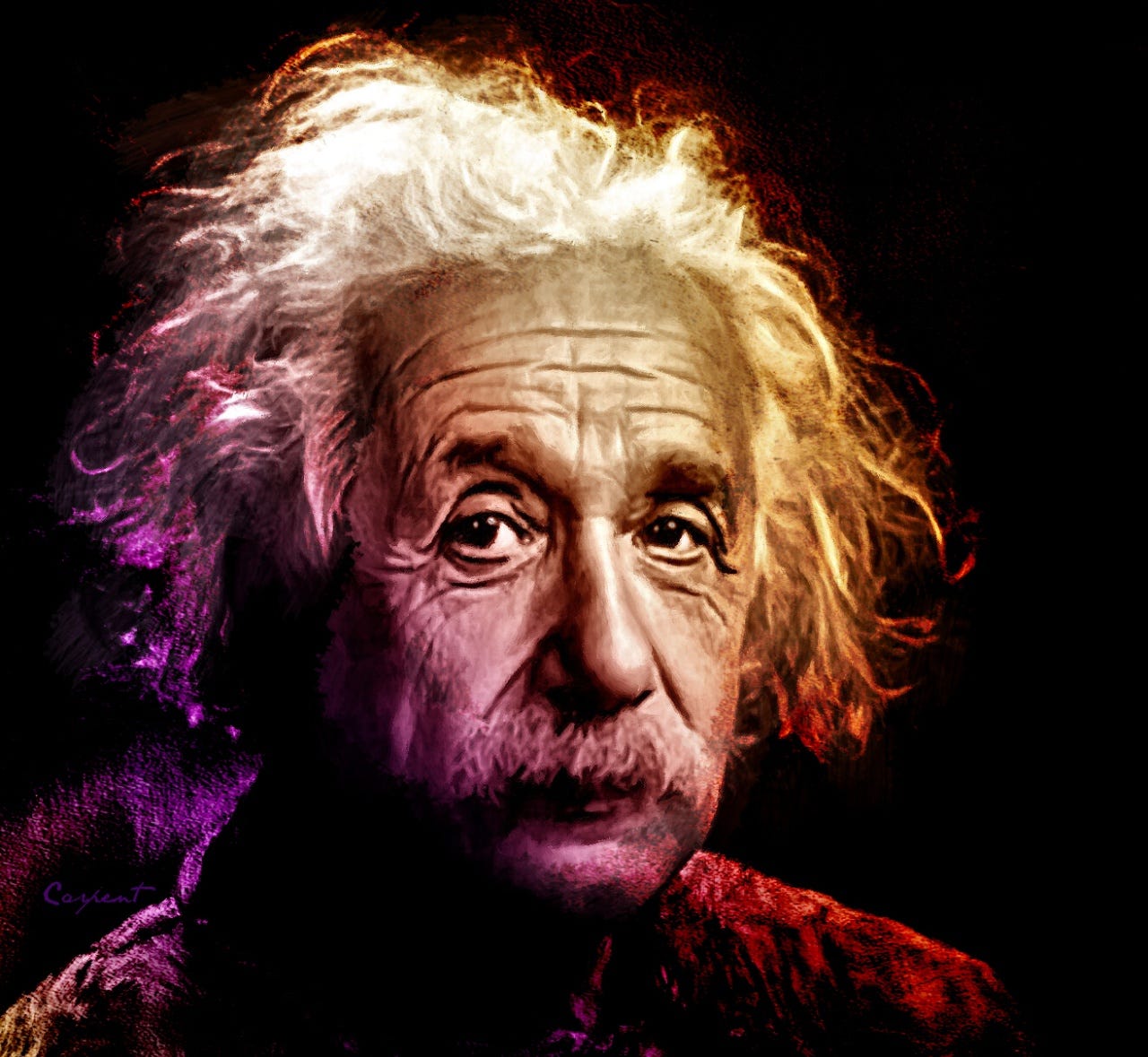

Galileo, Einsein, Benji: a rhetorical fugue.

This is a piece I’ve been tinkering with for a few months now. I kept thinking I would improve it, but I moved on to other ideas. Originally, it was going to be an introduction to a longer piece about a particular thought experiment to do with my (now former) downstairs neighbor. I think that I’ll try to finish that one next and publish it in the next couple of weeks. For the time being, I hope you enjoy. it’s a bit lighter in tone than what I’ve been up to lately.

I. The Prodigal Scholar

When I decided to go back to school in 2018 to earn a degree, I had no idea that I would end up majoring in philosophy. Despite having always had something of a philosophical bent, the latent (or at least dormant) intellectual curiosity that I discovered, at the ripe old age of 30, was of the scientific variety.1 So it was with visions of physics and cosmology—not metaphysics and epistemology—dancing through my head that I returned to Portland Community College after a decade-long hiatus.

After a few rounds of preliminary paperwork, I found myself seated across a desk from a kindly old academic guidance counselor.

“Well,” he said, glancing down at a printout of my rather uninspiring ten-year-old transcript. “Welcome back.” He looked back to me, his expression guarded and skeptical, like I was a mother who, after surrendering her malnourished and scab-covered child to the fire station on his first birthday, had shown up a decade later at the home of his adoptive parents, unannounced, expecting full custody. “I suppose we should talk a little about what you’re hoping to accomplish here, this time, what your interests are, potential majors. What brings you back?”

The wizened old fellow must have been at least 40. Good god, I thought to myself, in an instance of that phenomenon in which we project our most deep-seated and unconscious insecurities about ourselves, wholesale, upon whoever is in front of us. How depressing, to get to his age, and be stuck in a job like this. Always the bridesmaid, eh friend? A framed diploma on the wall announced my interlocutor’s bona fides—Master of Social Work—and I made a mental note to avoid the discipline at all costs.

When I didn’t immediately respond, he looked again at the transcript. “I’m just asking because it looks like you’re actually pretty close to finishing your associate degree,” he told me, “but you’ll probably need to retake a few of the courses you failed, depending on what your goal is.” Then, taking an almost apologetic tone, he added: “And, of course, it’s important to make sure that whatever happened last time—that caused you to lose steam and drop out—doesn’t happen this time around.”

My hubris evaporated; I felt suddenly uncertain in the presence of my lettered better. It was true, reader: this was not my first community college rodeo. I had taken a year’s worth of classes straight out of high school and another couple of semesters in my early 20s. Taken together, both attempts revealed a pattern that even a complete stranger could decipher with ease: strong start, mediocre middle, catastrophic finish. I was the runner who sprinted once around the track and then, my energy spent, walked a second lap before abandoning the race altogether without ceremony. Obviously, the advisor could not know the details, the contingencies that circumstanced my modus operandi, but I felt ashamed to realize that the man had my number.

“I-I’m—” I stuttered, “—i-interested in, maybe, physics?” I hadn’t meant to turn it into a question, but my register had risen a half-octave by the end of the confession. It did not inspire confidence in my guide.

Masking a grimace, he glumly studied my transcript and opened his mouth to say something before ultimately changing his mind. “Okay. Well, if you want to be a physicist, then the first step will be retaking Math 70 and Public Speaking. After that, you should really only be taking math and science classes until you transfer to a four-year.”

I demonstrated the extent of my mathematical literacy with the observation that this was only two classes, and shouldn’t I sign up for a few more? The counselor stopped me: “Look,” he said, taking pity. “You failed all the classes you attempted in 2011. That doesn’t mean you’re not smart, or that you won’t do well this time around. I just find that people in your situation do better if they start off slow. If fall term goes well, you’re more than welcome to enroll full-time in the winter. Sound good?”

It sounded fine. Honestly, I’m grateful to him—at that point, I was deflated enough that if he had given me any pushback whatsoever, I would have left and never returned. Instead, over the next year I finished my transfer degree (and, in the process, disabused myself of the notion that I might possess the requisite arithmetical acumen for physics) and enrolled at Portland State.

So it was that in January 2020, I found myself once again sitting in the office of an academic advisor. Like his junior college counterpart, he had a diploma hanging from the wall—also social work, but a Ph.D. His name was Tony; the first thing that I noticed about him was that I seemed to have caught him on a very good day. Reading over my transcript, he noticed and then effusively praised my dramatic turnaround. When I asked him about doing a double major, he scoffed. “Someone with your ability,” he said, grinning wildly and pointing to the transcript, which I had done much to improve since my return to the academy, “should be focusing on finishing your B.S. as quickly and cheaply as possible. You should really be thinking about graduate programs.”

I was flattered and (at the time) entirely ignorant vis-à-vis the structure and machinations of higher education. I didn’t actually know what grad school was, although I heard people talking about it occasionally. But Tony’s confidence in my “ability” and enthusiasm about my prospects made him easy to trust. After all, didn’t I, in my heart of hearts, believe myself to be extraordinary, talented, and yes, exceedingly able? If Tony and I converge so wholly on this most important matter, I thought, surely Tony knows best.

And so it came to pass. I told him my whole story, how I had been a bright and precocious child whose diamond was lost in the rough of a ruinous opioid addiction; how I had loved every class I’d taken in the past year: psychology, philosophy, physics, astronomy—even math—and so was having trouble choosing a major. Fuck if I didn’t tell him that Carl Sagan had, posthumously, changed my life, that the first four chapters of Pale Blue Dot—where Sagan writes about the Copernican revolution, the Roman Inquisition, the great demotion, and our species’ precarious tenure on the planet—had instilled in me a burning passion for the big picture, which was tediously earnest of me to tell this complete stranger, but also true.

Ever the consummate professional, Tony listened in rapt attention. He knew, he told me when I finally shut up, the perfect major for me: Liberal Studies, Portland State’s very own build-a-bear degree. Under the auspices of the unstructured, choose-your-own-adventure Liberal Studies Department, I could take any classes that interested me, from any of the university’s colleges (with a few exceptions—no math, but no loss), and all of them would count toward my degree. It sounded perfect. I was in.

The twist, gentle reader—and there’s always a twist—I’ve alluded to already. Do you recall how I seemed to find Tony in high spirits? Tony’s exuberance that day, as it turns out, was not solely due to his salubrious encounter with me, a guileless scholar virtually overflowing with academic potential. Rather, Tony had just given his notice; what I took to be an unattenuated passion for advising undergraduates was actually the incipient mania of a man for whom an entire year’s worth of bureaucratic obligations had just been wiped clean.

The form letter that arrived in my inbox a week later from Tony stated as much: Tony announced that he was leaving Portland State in order to devote more time to family and personal projects; Tony was grateful for his time with the university; Tony would not be joining us for winter term, slated to begin in less than a week.

He left instructions as to how his former charges should be divvied out to new advisors: psych majors go here, English majors there, and so on. I poured over the list looking for the Liberal Studies department, but there was nothing there. A thorough search of Portland State’s labyrinthine website revealed nothing. It was not as if the Liberal Studies department had been shuttered, its members absorbed into the university’s larger, better-funded departments; it was as if it had never existed at all. My heart sank. The Hogwarts Express had left the station, I realized, with me reeling and concussed in its luckless dust, a knot forming on my forehead where I had encountered no illusory wall at Platform 9 & 3/4, no magic, just the humiliating solidity of corporeal brick.

II. Gedankenexperiment

With few exceptions, life’s great vicissitudes are legatees of the butterfly effect. Car accidents are a prime example: if only I’d left sooner (or later); if only the dog hadn’t (or had) pissed on the floor. A minute’s delay would have changed everything, and vice versa, ad infinitum. Or, less morbidly, the chance encounters—say, at a coffee shop—that turn into great, life-defining love affairs.

The causal fulcrums upon which life is leveraged are almost never recognizable to us at the time except, perhaps, as an inchoate sense of unease or excitement, dread or anticipation. Even in hindsight, we will only very occasionally be able to identify a strict causal progression, step one leading to step two, and so on. Thus it is of at least a passing interest (well, to me) that I can identify the exact decision that led to my (ultimately) opting out of Liberal Studies and declaring instead as a philosophy major.

In my second term at Portland State—COVID-19 having only just turned the entire student body into distance-learning refugees—I wrote about the role of thought experiments in Galileo’s scientific discoveries for PHL 470: Philosophy of Science. You’re probably familiar with the term “thought experiment.” In recent years, thought experiments have bled out from a gutshot academia onto the culture at large. Television series like Black Mirror take inspiration from various philosophical thought experiments, sometimes to great effect. The Good Place is less subtle, wearing its philosophical influences proudly on its sleeves; sometimes its characters are literally just reciting thought experiments to one another, reading real-life philosophers in a college classroom, except in heaven. Video games like SOMA go that step further by introducing the variable of player agency into simulated thought experiments, which really brings the thought experiment to life.

There was a problem, though, with my essay on Galileo, I realized after reading over the first draft. It was all correct; the information was organized well enough. There were no typos, no major grammatical issues. Its issue was the same one plaguing the preceding paragraph in this very newsletter: thought experiment, thought experiment, thought experiment. The phrase “thought experiment” was overused, repeated ad nauseam until it broke the cadence of my writing. It sounded clunky and sophomoric. But what to do about it? Vaguely recalling something I’d once read, I knew that the term “thought experiment” had been coined by Einstein and that it had a special name in German. So I googled it; the German phrase was gedankenexperiment, “gedanken” meaning “mind” or “thought” and “experiment” meaning, well…2

I was torn. Over the next two years, I would acquire a taste for writing in the fussy argot of academic philosophy, but doing so is akin to training one’s palette to enjoy black coffee, bourbon, or tobacco. It required that one take that first, disgusting sip, to inhale that repulsive preliminary puff. Starting out, it’s normal to feel a little green around the gills, a little sick to the stomach. I waded into the rewrite:

Surveying Galileo’s prodigious body of work in physics and astronomy, it is all the more remarkable to learn that his attitude towards experimental confirmation—that hallmark of science—was inconsistent, even flippant. Galileo discounted experimental results that conflicted with his theories, writing off discrepancies as “unnatural accidents” or due to “secondary causes” (qtd. in Losee 51-52). Elsewhere, he claimed experimental results that—in hindsight—betray their gedanken pedigree.

I gagged, a little. But as I reread the paragraph once, twice, three times, the German word no longer stuck in my craw, each time going down more smoothly than the time before. On the fourth read, I realized, it started to sound almost good.

Thanks for reading. I hope you’ve enjoyed this episode of White Elephant. As always, you can reach me at benjimahaffey@substack.com, where I accept positive criticism and softball questions.

Or, as it used to be called, “natural” philosophy.

“Experiment”