The Ordering of Things, Vol. III: Simple Human

Coparenting with Alexa, beta-male nesting, and keeping house with Sam Harris.

This newsletter is a part of The Ordering of Things, a series of essays about my favorite things from 2022. Each is standalone and can be enjoyed without reading the others, but if you’d like you can read the first one here and the second one here. Thank you to everyone who has read and subscribed during the inaugural month of the newsletter.

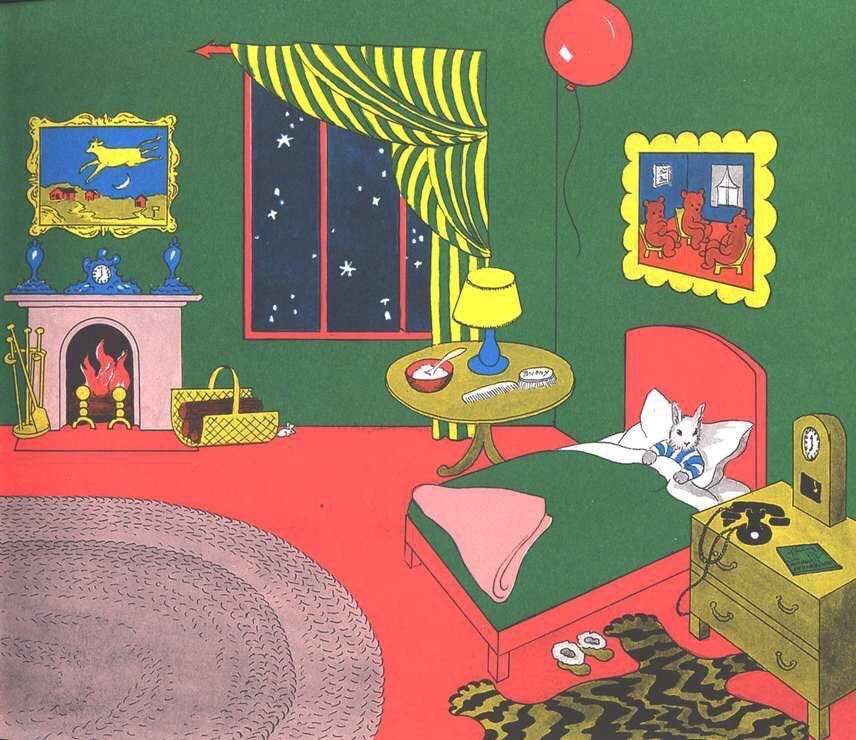

“In the great green room,” I read aloud to my son, his eleven-month-old head so close to my mouth that his whispy baby hairs tickled my lips, “there was a telephone. And a red balloon. And a picture of…” Here, I paused, waiting a beat for him to turn the page. “The cow, jumping over the moon!” For this line, I quieted my voice so that I could emphasize the words “cow” and “over” while still keeping my volume low, the cadence soothing and hypnotic.

The seventy-five-year-old children’s bedtime story Goodnight Moon is fast becoming a contender for one of Graham’s favorite things of 2023. Probably mine as well. It’s a fantastic little book, simple and beautiful—not flashy, no gimmicks, just dreamy, understated magic and elegant sweetness.1

“And there were three little bears,” I went on, “sitting on chairs—Graham, do you want to turn the page for me?—and two little kittens, and a pair of mittens.” We continued the inventory: a toyhouse. A young mouse. Comb, brush, mush. Hush, whispered. Graham was sleepy. He stopped turning the pages, squirmed in my lap and rested his arm on my wrist. “Goodnight, room,” I said. “Goodnight, moon. Goodnight cow jumping over the moon.” The first bit of Goodnight Moon is an exercise in list-making, pointing out, and naming. The rest is a reinforcement of object permanence; we say goodnight to all of the named things with the implicit expectation that they will be there again in the morning upon waking. It was to this latter portion that we had arrived, where the book’s already quiescent meter becomes almost narcotic.

“Goodnight light,” I whispered, “and the red balloon.”

Without warning, our Echo Dot speaker emitted an abrupt and grating chime. At the same time, both the overhead light and bedside lamp turned on and changed color, illuminating the bedroom that a moment before had been dim and cozy in a dystopian red glow. The spell broke: the drastic contrast roused Graham from his somnolence. He sat up, smiled, and began to coo and wave frantically at the crimson orb overhead.

From across the bed, my wife glared accusingly at me. “It was your watch,” Hannah hissed, referring to my treasured Apple Watch. I had no retort; it had indeed been my watch, collaborating with my Alexa and my Phillips Hue smart lights. Such is the lot of we hubristic tenants who have, like gods, breathed the fire of intelligence into our formerly-insensate homes, fashioning them after our own image by giving them eyes, ears, and voice. Our smart home was working as intended.2

During Hannah’s last trimester, the reality of Graham’s imminence finally breached whatever strongholds of delusion remained in my mind. The first trimester had been mostly blushing romance:3 do you hope we have a boy or a girl? Then: what should we name him? Even throughout most of the second trimester, our due date seemed far off and fantastical. Life was relatively normal. I applied to graduate school; we celebrated the holidays with family.

In January, though, moments of panic started to descend with escalating frequency. Their typical duration increased likewise, emerging initially as brief spasms of sheer terror, evolving into day-long meltdowns wherein Hannah and I would talk each other off ledges, until finally, the fear integrated fully into our beings, a chronic and constant baseline but manageable, not debilitating. It was during the latter stage that my dread motivated me to act: in a fit of 21st-century beta-male nesting, I cleaned the apartment to its bones, finding and removing refuse dating back to before my tenure.

I fixed things that had needed repairs for years. The rotation plate in our microwave had shattered circa 2017 and was never replaced. When I decided to find one, I was ashamed at how easy it was—five years lamenting our immobile appliance, which invariably heated its contents unevenly, solved in five minutes on Amazon. It arrived less than 48 hours after I decided to solve the problem.

It was a minor but pivotal victory, setting the tone for what would become my very own march to the sea. I think that, in hindsight, because there really is so much of life that is outside of our control, I had been living under the illusion that agency itself was a fiction. If something in our home was hideous, broken, or actively dangerous, my general modus operandi was to give it a wide berth. No need to tempt fate, I had thought.

But the microwave plate changed all that. With the zeal of a man whose life sentence had been commuted, I set about making our home more liveable, less awful. I took the busted particleboard closet doors off their hinges and replaced them with fresh curtains; while in curtain-installing mode, I remounted brackets above our bedroom window and placed upon them a sleek new rod, from which I hung sleek new blackout curtains.

Growing ever more sure of myself, I risked life and limb in the realm of electrical repairs. The primary burner on our stove had been on the fritz for years; a month ago, it had stopped working entirely. C’est la vie, the old me thought, dourly acknowledging that nothing lasts forever. I made do with an air fryer and an instant pot. The new me—the dad me—took the damned thing apart and scrubbed out a decade of petrified grease before installing new electrical housing, heating elements, and chrome stove guards. How they shined! With the heat set to high… oh, if you could have seen it, seen how the elements glowed! A pot of water that before would sit cold for eternity now bubbled and boiled over if we looked away for even a moment.

In the midst of my nesting frenzy, an unlikely guiding principle emerged. One of my best friends has a tattoo on her arm, a lyric from the band Frightened Rabbit. It reads:

make tiny changes.

This became my home improvement philosophy, my wu wei, a kind of domestic Tao. I focused on finding friction and removing it. Sure, Graham wouldn’t have a nursery. We couldn’t afford a bigger place; there would be no $1700 robot bassinet. I accepted these constraints and concentrated instead on sanding off the rough edges of the mundane places in our home that we used every day. My aim wasn’t necessarily to create time-saving processes, although many seconds were saved. Rather, I wanted to convert seconds of frustration into seconds of ease, believing they would add up, accrue interest, and amount to an easier, happier life.

Philosophy thus articulated, my next project applied the same logic to aesthetics. Our apartment is mostly one space, which was for too long dominated by an overbearing, gold-and-white pendant light that hung from a gaudy, bronze-enameled chain. Being bowl-shaped, it couldn’t illuminate more than the circle immediately underneath, which it lit up like an industrial spotlight; its homey atmosphere was that of a black-op interrogation chamber. When I first moved into the apartment, I fantasized about replacing it.

“How hard is it to change out those pendant lights like the one in my apartment?” I asked my mom one afternoon over the phone.

“Well…” She thought for a moment, muttering some calculations to herself. “It’s not exactly easy.” And that was that. It was impossible, she’d told me. No different, really, than hoping that my acceptance letter to Hogwarts was still on its way, had been lost in transit, that any day now a disheveled owl would arrive, Dumbledore’s personal apology tied to her foot.

But as I had proven to myself with the microwave plate, I was capable of making the impossible not just possible, but actual. I was Sherman crusading through confederate Georgia, the earth scorched in my wake and the lights of Savannah brilliant upon the horizon. At this point, only a failure of will could save that tacky eyesore, that tyrant. Such was my mindset at the Home Depot, where with shaking hands I selected a modern, lantern-style pendant with a black ceramic chain and an Edison bulb to go with it. It cost me $50. When I got home, I turned off the electricity at the breaker box, watched some instructions on YouTube, and set about my work.

Mom was wrong. It wasn’t impossible. The installation didn’t go perfectly—there were false starts, the chain was too long, had to be cut and rehung. The old wiring in the ceiling was coated with thick globs of paint and needed to be stripped to fit into the new fixture. But before long, I was done. I flipped the breaker and the apartment was bathed in a soft, benevolent light. It was beautiful.

Like the God of Genesis, I surveyed what amounted to a week’s worth of work and saw that it was good. So why then did I feel unentitled to a Sabbath? I felt proud of myself, but also a little sick to my stomach. I had lived here for almost ten years, and I made it more livable—by an order of magnitude—in a matter of days. It cost almost nothing. There was a metaphor for my life there, looming, conspicuous in the tasteful glow of the Edison bulb.

I think that it was this unease that spurred me on. Over the days and weeks that followed, gradually, unconsciously, I forsook my philosophy of wu wei, allowing myself to be seduced by the dubious blessings of modernity, the inventions—the products—that promise to make our lives easier, simpler, better. I brushed off a first-generation Amazon Echo Dot that was collecting dust on a shelf and bought her a sister for the bedroom. Bluetooth-enabled, color-changing lights for every room; even the brand-new Edison bulb, with its soothing, candle-like incandescence was exchanged for a smarter, uglier version of itself.

“Alexa, nightlight,” I demonstrated for my pregnant bride. After a moment of lag, the apartment stuttered to life, shimmering a lethargic red. The drama was compromised by the daylight pouring in through the windows, but still.

“Well?” I asked.

“Cool,” Hannah said.

“Yes,” I said. “Very cool.”

If you are lucky, when you’re going to have a baby, other people will buy you much of what you need. One of my professors and his family bought us the stroller we wanted. My brother and his wife gave us the (very expensive) baby monitor we asked for. Some of the things that we asked for and thought we would need, we ended up not using; other things that seemed silly or precious became items we couldn’t live without.4

The only thing that we asked for and then returned was an Ubbi, a one-trick pony of a diaper pail designed with a single, uncompromising goal: to contain the smell of poop. Pneumatic rubber gaskets; a sliding lid to “minimize air disruption.” And—bonus—it doesn’t, unlike some of Ubbi’s competitors, require special bags. Any old trashcan liner will do. To expecting parents, this sounds reasonable. After all, who likes the smell of poop? Who wants to worry about keeping an inventory of diaper-pail liners, separate from their ordinary garbage bags? It’s implied that that’s how those other pail peddlers get you: lure you in with a reasonably-priced contraption and then you’re on the hook for a lifetime subscription of obscenely expensive proprietary bags.

“It doesn’t have a foot pedal thing,” I pointed out. “You need a free hand to use it.” Hannah had been lukewarm on the Ubbi; we exchanged it for a Simple Human trashcan.5

The Simple Human uses special bags. I panicked at Walmart when I saw the price of ordinary garbage bags. They were like, $12 for 100. I pulled out my phone, right there in the aisle to see how they compared, per liner, with Simple Human. Fuck, I thought. They’re almost four cents more than the generic ones—that is how they get you. It doesn’t seem like much, but a year of daily use… 365 days, four cents a pop, round up to five, carry the two… My chest felt tight; I could feel my future collapsing around me, pictured my family on the street, our few remaining possessions tied up in Simple Human bindles.

Oh. I exhaled. It would take more than a year of daily use before it amounted to even twenty bucks. I could live with that; the can is nice. It has a foot pedal and is made of stainless steel. The bags are a breeze to change out. It’s not a pain in the ass.

This is the kind of expense happily absorbed, I thought, by the upper-middle class, people for whom time is the real commodity, and then—because I had been listening to his podcast that day at work—people like Sam Harris. Once I’d made that association, I started to notice something: at the beginning of his podcast, whenever he had some piece of marginalia to announce unrelated to the podcast proper, he would say, in his once-in-a-generation, made-for-radio baritone: “Okay,” exhaling a single deep breath. “Time for a little housekeeping.” I pictured him fluidly changing out a liner. “Okay.” He was tying up the full bag with Simple Human’s ample and sturdy built-in drawstrings. “Time for a little housekeeping.” Sam Harris noticed he was almost to the end of the pack. Without a second thought, he tapped a button on his phone to order more.

The Simple Human was more than just a marvelously efficient diaper pail; it was more even than a psychic window into the personal life of Sam Harris. During those difficult first months, it became an emotional support, a grounding totem. Oddly, it was the expense that I did not spare that brought me succor. The decadence of it never wore off. On paper, custom bags for a glorified shit bucket are the very definition of excess, a luxury convenience for the wealthy that ought to be withheld from plebeians such as myself. Yet they were mine for less than I’d spend on a pizza, the kind of money I might grudgingly donate once a year to Wikipedia. Whenever I pulled out a fresh liner, I’d thumb through the pack like prayer beads, my rosary the syllogism:

If a father spends $20 a year on designer diaper pail liners, then he is doing okay.

I spend $20 a year on designer diaper pail liners.

Therefore, I am doing okay.

The Simple Human did what nothing else could: it provided ironclad, deductively-valid proof that I was a good dad. I began to feel better and better about the decision to exchange the Ubbi. I started to look forward to the daily chore—the daily ritual—of changing out the liner, which conditioned me to look forward to Graham’s daily constitutional.

“Alexa,” I heard Hannah in the bedroom. “Log a poopy diaper.” Unbidden, a pavlovian burst of saliva flooded my mouth and I sprang up to make my way to the bedroom. With one hand, Hannah wiped the last flecks of feces from my son; with the other, she deposited Graham’s most recent bowel movement into the Simple Human with staggering ease.

“Let me get that out before it stinks up the room.” I gestured toward the diaper pail.

“Oh, that’s fine—” Hannah started, but it was too late. I couldn’t hear her over Sam’s voice in my head. Okay. Time for a little housekeeping.

I nodded, smiling to myself as I expertly removed the liner from the pail. Indeed it is, Sam. Indeed it is.

Questions? Comments? Anonymous tips to CPS? Send them to benjimahaffey@substack.com. As always, thanks for reading, and thanks to my brother, Joseph Mahaffey for the White Elephant logo. Image credit: illustration by Clement Herd from Goodnight Moon.

Up until recently, though, it was a little too cerebral to consistently hold his attention. This technicality disqualified it from inclusion on the 2022 list.

To the smart-home savvy, something about the scene should not add up: usually, Alexa is dormant until she hears a “wake word” for which she is always listening. Designed, I assume, to avoid unanticipated consequences like the ones depicted above, I had taken it upon myself to bypass this Bezosean safeguard. With the mere tap of my Apple Watch, I can whisper commands to a fully-alert Alexa; when Graham is sleeping, I don’t want to have to shout “Alexa!” from across the room to control a speaker, a light, or the air conditioner.

Graham had tapped this button without my knowing it. The words “night” and “light” were the command for a routine I had set up that turns every light in the house both (1) on and (2) red. (The “red balloon” was a happy accident, or a red herring, depending on your point of view.)

Well, and morning sickness.

Off the top of my head, I’m thinking of just one thing: a wipe warmer, a little humidifier that keeps the baby wipes within it nice and toasty. It seemed like a bad idea at first—who wants to condition their infant to expect only body-temperature butt wipes?—but, yeah. When you have a kid, suddenly anything that even might contribute to their comfort becomes worth its weight in gold.

The brand name “Simple Human” is stylized as simplehuman. That triggers my OCD, though, so I’ll write “Simple Human.”