1992

On death, grief, and the paradoxical consolation of afterlife.

This essay was written more or less in its entirety last November, before I started White Elephant, which is part of the reason why it’s a little different, stylistically and thematically, than what I’ve written and published so far specifically for the Substack. I’ve been told that it’s quite dark, and although that wasn’t my mood while writing it, I have to agree that it has turned out that way. So, trigger warning, I guess.

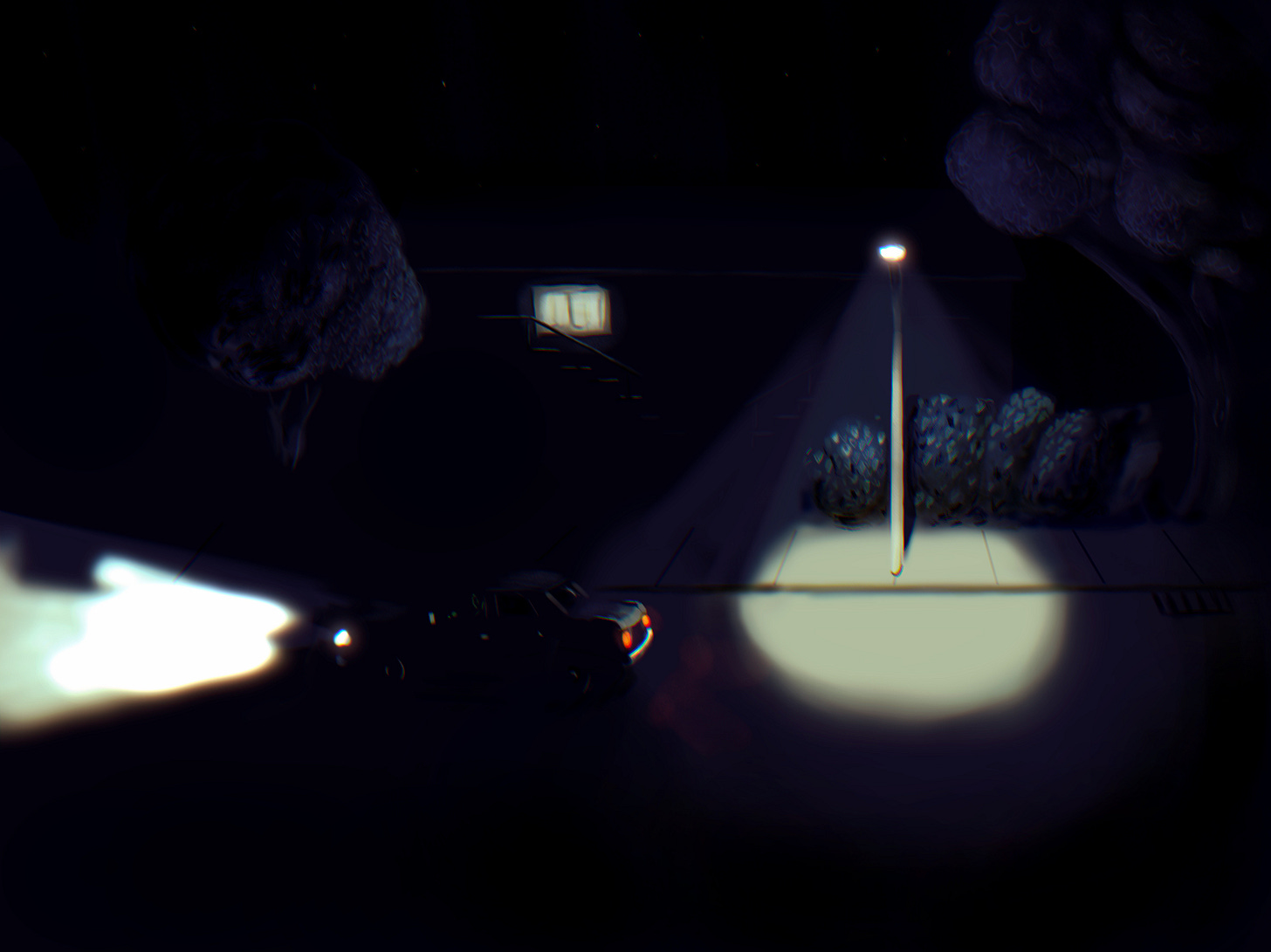

Additionally, apologies to those of you who have already read it, and thank you if you’re one of the folks who offered me feedback on the rough draft, especially Alex Kelly. Thanks also to my brother, Joe, for creating the accompanying artwork for this piece.

I’m six years old, lying on my parent’s bed in my childhood home in Portland, Oregon. I’m transfixed by a feature of their bedroom that I take for granted: the way that, when a car passes on the street outside, its headlights cast shadows along the upper wall that look animated—a spontaneous cartoon. This phenomenon occurs only after the sun has set, infrequently enough that it remains novel, but not so rare as for me to lose interest. I’m neither happy nor unhappy. My thoughts are unobtrusive; they do not announce themselves as thoughts. I just am.

My mom and dad are there, talking about Uncle Russ, my father’s younger brother, who has cancer. The cancer had started in his leg, which the doctors wanted to amputate. My mom is crying; I ask her what’s wrong. “Oh, baby,” she says.

She sits down next to me on the bed and a new sequence of light and darkness slithers across the wall and up the ceiling until it disappears almost all at once. Each of the shadow cartoons is a little different—some barely crawl past, others distort like a VHS tape on fast-forward, depending on whether a car is going below the speed limit or above it—but their general structure is always isomorphic with the hard angles of the window’s wrought-iron frame and the blinds that only partially obscure the glass beneath. This hard-boundedness of the shadow puppets is further limited by the position of the street itself. Light can only be projected from the east or west—people coming, people going—and, though it can occasionally differ depending on the luminosity of the headlight projecting it, these differences are too subtle for me to distinguish.

“Are they going to cut off his leg?” I ask. This, so far as I understand, is the unimaginable bargain that Uncle Russ had, up until now, rejected.

My mom isn’t crying anymore. “No, sweetie. It’s too late for that now, so it wouldn’t help. Uncle Russ is very sick. His cancer spread into his lungs. The doctors don’t know when, but he’s probably going to die very soon. Daddy’s going to go be with him now.”

Another car passes, this time from the other direction. The light on the ceiling starts out bright and pointed before expanding, crisscrossing; gridded honeycombs of light and dark that flicker like a film projected from a reel until the room is washed in soft yellow warmth, splintered by shadows bigger than I am. Someone going. Then the light disappears, and I hear the car fade into the night. I imagine my uncle’s cancer like this: spreading and diminishing, here until it is not.

Once it is dark, I think of something to say. “Will Uncle Russ go to heaven when he dies?”

I can’t see her face, but there’s no hesitation in her reply. “Yes, baby. When Uncle Russ dies, he’ll be with Jesus in heaven.”

When I was much older, I would recognize this for what it was: not strength, not quite, but stoicism or its cousin, coupled with the impulse to conceal from me death’s unspeakable mystery. Mom was acquainted with loss. Her little brother died when she was just a little girl, and then her father, too, unexpectedly—a heart attack—before she graduated high school. I don’t remember what happened next. Maybe I started to cry; maybe I asked to play Nintendo. Perhaps Russ died that very night. Perhaps he lived on for a few days or even weeks.

In my memory, though, this was the moment when my uncle died. I hadn’t known him; I don’t remember ever meeting him, although I’ve seen photos of him holding me when I was a baby. He and his family lived far away, so we didn’t see them often, and then we didn’t see them at all. It was too late: he was dead, forever. No—“forever” is a comfort—my mother would love me forever, and so would Jesus. So would my dad. Death is a never, and we would never see Uncle Russ again.

My father was devastated. He was just two years older than Russ. He shared that bond that only exists between brothers born in rapid succession—a childhood canon of mutual experience, shared emotions and memories, the exquisite, almost ecstatic joys of brotherhood and its bitter feuds that, like Portland snow, might conceal the entire world for a single evening but melt at dawn, revealing a landscape fundamentally unchanged, its bedrock permanent and enduring, its alterations exposed for the contingent illusions they had been all along.

Back then, my father (and, by proxy, the rest of our family) was a Christian. This meant that his grief was frustrated by its very consolation. The Gospels promised us that death had been neutered of its inimical sting and that victory, so implausible, had been snatched from the grave itself. This, to say the least, is no small succor, if we believe—and I think that my father, on some level, really did believe—that one day we will see with new eyes our beloved dead, and that they will have been made whole by God, their cancers excised, their limbs rebuilt; that upon death—after the cessation of the body and the dissolution of self—we will be relieved to discover that consciousness, rather than terminating, actually expands, redeemed and completed in an infinitely richer and more perfect reality.

For the unbeliever, death is apocalypse, catastrophe, loss absolute. Faith takes death’s leaden totality and transmutes it. Nullification, undoing, and annihilation become infinite creation, infinite bliss. Furthermore, this alchemy is wrought with a single reagent: the perfect blood of Christ, the Lamb of God, spilled at Calvary. For the faithful, the triumph of Easter strips grief of its rationale, renders real mourning incoherent. The believing dead are merely asleep, promised the apostle Paul. Sorrow ye not as those without hope; the dead in Christ will rise. Is this the price of consolation, or consolation itself? I don’t know. It depends on what grief is. It seems to me that grief is a necessary concomitant of love, or perhaps even that grief just is love, deprived of its object, and mourning its proportional expression. To the extent that our grief achieves for us some measure of catharsis, Paul’s epistle requires that we delay our gratification indefinitely.

I don't know if this occurred to my father—nor do I know whether he felt deprived, his grief frustrated or stymied. In the end—or at least until the end—it probably doesn’t matter. In just two years—before he could even acclimate to his grief over Russ—his older brother, Larry, died. His dad, my grandfather, lived just long enough to watch his boys die before succumbing to cancer himself. Dad slipped into a deep depression, the kind of bottomless well from which you’re never entirely extricated, though neither can you make it your home. Instead, it comes to reside in you. You internalize the dank, mineral scent of loss; you recall a sliver of receding light, but can’t remember where it came from.

I have heard it said that death makes a mockery of life. It is ever-present, and casts a pall of absurdity over not just everything that the living love and value, but of value and love themselves. Death is the negation of all possible meaning; it transcends propositional logic entirely, as brute as the spatiality of matter’s three-dimensional extension, primitive as time’s unidirectional flow. Death comes before, the necessary condition upon which the possibility of belief, knowledge, and consciousness depend.

To my parents’ credit—whether intentionally or unconsciously—they made every effort to give me a long childhood, to preserve my innocence, unburdened by morbidity and mortality. And, at the conceptual level, they succeeded; death remained for me an exceedingly abstract infinity, and—when those instances of it with which I was acquainted crossed my mind—it was to wonder, vaguely and indulgently, what Russ and Grandpa were getting up to in a vague, indulgent heaven.

A childlike faith in heaven is incompatible with the notion of death, and so from exposure to true death, I was spared. Dad didn’t tell me until much later how he had begged his atheist father, on his deathbed, to accept Christ’s gift of eternal life and thus secure for himself a place at God’s side whereupon they would one day be reunited. I would be a man before I learned that the proximal cause of Russ’s death had not been his cancer. Rather, it was a morphine overdose, the palliative administered by his older brother, who held his hand as his breathing slowed and then stopped.

Despite their best efforts—efforts which I do not begrudge them—my parents could not rid the garden of all its serpents. Because death is the ultimate collapse of order within an unraveling system, and because we exist in a universe populated exclusively by these entities—discrete processes all, with boundaries at first porous, then permeable, until they disintegrate altogether—death is omnipresent. So even before Uncle Russ died—my first death proper—I had been troubled by death, by which I mean only that particular feature of existence that forbids all permanence and mandates eventual dissolution.

Returning to kindergarten after Christmas break, our teacher welcomed us back to school. “The year is no longer 1992,” she explained to the class, emphasizing the word two.

“The New Year means that now, it’s 1993.” Inexplicably, I was thrilled with this knowledge, and that evening, I couldn’t wait to share it with my mother—did she know that it was 1993? She affirmed that, yes, it was now 1993. During the high of the revelation I blurted out: “How long until it will be 1992 again?”

It took a moment for her to register, and then she said—with almost callous flippancy—that it would never be 1992 again. A beat: then I wept, threw a tantrum, howled until I choked on snot and tears. This was my first acquaintance with death, although back then, I lacked any conceptual framework or context with which to give my inchoate grief expression or form. Nevertheless, the weight of the thing never changes: the gravity of a collapsing star, the realization of finitude, of transience; of the fact that an egg beaten cannot be unscrambled; that time moves forward, never backward; that we remember the past but only anticipate the future. The sudden, inarticulable consciousness of the entropic structure of a cosmos in which order decreases unceasingly, and the way in which moments spill like water from grasping, clutching hands until, inevitably, it is all gone, squandered and unrecoverable.

So it was: 1992 had died, and in my naivete, I had celebrated it. As a boy of five, I did not have the constitution to grieve indefinitely, and like a good mourner I eventually allowed myself to be consoled by my freshly-chastened mother. But this is the thing about grief and grieving, which is known to all who grieve: although mourning ends, because it must, grief does not. Grief changes, of course—it would be a cruel paradox for grief to be the one immutable feature of our predicament—but, as those who have lost siblings, parents, lovers, friends, or children will tell you, grief is ceaseless. Like ink spilled on a notebook, the pages of life must be turned, but the stain of grief is permanent, becoming a palimpsest impoverished by a loss that cannot be effaced.

As it extends temporally, grief is at best diluted. The relentless flight of time’s pitiless arrow entails that, when someone dies, we will only ever grow farther away from them. No matter how close we were to them in life, if we go on living, there will only ever be more moments in which they are absent, never fewer. The fraction of my life contained within that year—1992—has been diminished by the procession of months and years that followed, but it cannot be made smaller. Grief is acute, then chronic. First it is concentrated, excruciatingly bright, the only thing in the world, but grief grows dimmer as it expands: a cancer, originating on an extremity, hot and painful on an arm or leg. Soon enough, however, it permeates the body, malignant clusters of ruined cells in the liver, brain, lungs, proliferating exponentially, too quick to cut out.

As always, thanks for reading. If you have comments or questions, send them to me at benjimahaffey@substack.com. Image credit: original artwork by the exceedingly talented Joseph Mahaffey.

Wow. Excellent. Thanks for sharing.